HASTA: Frederick J. Brown 1945 - 2021

February 2, 2021 - Katie Bono for HASTA

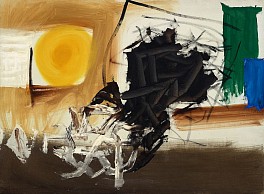

Frederick J. Brown had an incredibly prolific career throughout which he moved fluently between abstraction, figurative painting (particularly portraiture), landscape painting, ceramics and collage. Particularly in his early career many of his vivid and evocative brushstrokes recall de Kooning: Brown’s longtime mentor. In fact, Brown famously painted de Kooning, depicting him in bold swaths of primary color that recall de Kooning’s own style and eclectic personality. Early on in Brown’s career he was particularly influenced by de Kooning and the German school of Abstract Expressionism. After his early abstract works in the 1970s, Brown began to introduce figuration into his work in the 1980s. While most of his career did have a largely figurative focus, the emotive influence of Abstract Expressionism carries through the body of his works.

Brown was born in Georgia on February 6th, 1945 and grew up on the South Side of Chicago. He credited his family for surrounding him with color; his uncle repainted cars (Brown would help him mix the paints) and his mother was a baker who specialized in cake decorating. His mother’s influence in particular caused Brown to have quite a tactile relationship with color and he claimed that painters were “people who love paint” particularly the feeling of paint. Another formative influence was the community of jazz musicians that Brown met through his father. Brown’s relationship with music cannot be overstated; his bold, vigorous works often produce synesthetic experiences and Brown listened to music while he painted, citing it as a creative catalyst for his painting process. He attended Southern Illinois University where he studied art and psychology.

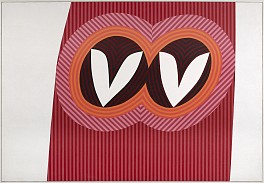

In 1970, Brown moved to SoHo to pursue his painting career. At this point he was focused on musical and abstract influences. In 1977 he collaborated with the Adler Planetarium to produce his wonderful work Milky Way that exemplified the galaxy as it was understood in the late 70s. He hints at the spiral shapes of the galaxy while imploring the viewer to imagine other aspects of the Milky Way. This work and several of the studies leading up to it showcase his aforementioned tactile relationship with paint and color. Dabs of paint throughout Milky Way almost inspire a visual sense of touch. Another painting of his, Elephant Skin was actually painted so that the paint itself would feel like an elephant’s skin. Brown’s idea that anyone could even feel one of his paintings was indicative of his egalitarian approach to art. In 1985, Brown taught in China at the Central College of Fine Arts and Crafts - during his teaching he sought to embody what he considered to be an authentic American experience. He imported his entire studio and would work for 13 hours at a time to give his students an idea of the intensity of his process. His teaching experience was followed by an exhibition of his works in 1988 at the Museum of the Revolution in Beijing. He was one of the earliest Western artists to exhibit in China and at the time he was the largest exhibition of a Western artist to date. He was commended for the moving sense of his works and was an exemplar of cross-cultural relations at the time.

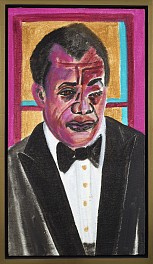

In the late 1980s, Brown began a series of portraits of jazz musicians. This series was significant in the sense that it exemplified the excellence of Black musicians and demonstrated Brown’s own excellence as a Black painter. It was on Brown’s part, an effort to make sure these artists were appropriately memorialized. Brown would listen to the artist’s music as he painted their portrait and this influenced the visuals of the painting. In his work Duke Ellington, Duke’s large and soulful eyes are the immediate striking characteristic. But if one takes into account the surprising pockets of color (the blue tones at the base of his eye, the red across one cheek, and the dash of yellow on his bottom lip) and the erratic curves that constitute his face, both these elements are reflective of the erratic and surprising nature of Ellington’s compositions. Another portrait Brown painted, Sarah Vaughan is a contrast to Ellington’s portrait. Vaughan’s face is all vibrant color and smooth elegant lines that recall the cadence of her voice. In her rendition of “Somewhere Over the Rainbow” it is quite clear how her voice translates to her portrait.

Beyond these projects, Brown worked on a number of spiritual and religious works and reworked common themes like the Last Judgement and the Virgin and Child. He painted a number of bright folklore-like works that were simply meant to inspire joy after his experience in a drab hospital - it showed his propensity to use art as a vehicle for an emotional experience in the viewer. Another notable work of his, History of Art is a series of over 100 canvases representing important paintings in Art History. The series effectively recasts the monochrome canon of Art History into a vibrant and diverse set of new subjects. Many of the works are either infused with new vigor or feature people of color in portraiture. Brown said once in an interview to the Smithsonian: “I think my heritage has a great significance to the images I produce, but you can limit people with a name or a title to only serve one group. When you see my work, you can tell it is done by someone who is Black. But, I want to provide as many beautiful things to the world as I possibly can.” Indeed, Brown’s wide artistic achievements left a legacy of accessibility and facilitated a democratization of art. Frederick J. Brown died of cancer in 2012 and is survived by his wife Megan and his two children.

Read More >>